Remembering Traveller

Remembering Traveller

By Nelson McKeeby

Remembering Traveller

By Nelson McKeeby

(Note: Nelson McKeeby is a science fiction author whose new book series, the Tea Merchants (The Tea Merchant), has recently been released, causing some of his old writing to surface about role-playing games. This article is posted with permission.)

Before TravellerFrank Chadwick(1) developed a passion for wargames and military history during his high school years. This interest led him to co-found the Illinois State University (ISU) Game Club with Rich Banner(2), a graphic artist. At the university, the club focused on wargaming and began designing their own games to support their hobby. Their work, though, caught the attention of their professors, who lobbied for funding to support it, leveraging the idea of gaming to teach a range of subjects, including history. The result was a university-funded project called SIMRAD (SIMulation Research And Design), which aimed to create educational games for use in the classroom.

The ISU Game Club and SIMRAD saw two additional important additions: Loren Weiseman (3) and Marc Miller. Marc W. Miller served in the United States Army and subsequently used G.I. Bill benefits to continue his education. He was interested in returning to the military and joined the ROTC program at the University of Illinois, but the post‑Vietnam force reductions altered those plans, and he transferred to ISU. In 1972, he enrolled at Illinois State University and joined the game club and the college simulation lab.

Miller, Chadwick, Banner, and Wiseman established Game Designers’ Workshop (GDW) on June 22, 1973, to sell games based on their work at the ISU Game Club and SIMRAD. They immediately released two games that launched the company to profitability and acted as a springboard that would establish Traveller as the first successful science fiction role-playing game.

Triplanetary, a classic science fiction board wargame, was originally designed by Marc W. Miller and John Harshman and published by Game Designers' Workshop (GDW) in 1973. Its design was groundbreaking for the time, eschewing traditional "move-and-shoot" mechanics in favor of a realistic vector movement system that accurately simulated Newtonian physics. Players would plot ship courses on an acetate overlay, accounting for inertia and gravitational effects, a mechanic that made the game as much a scientific simulation as a wargame. This innovative approach, combined with its unique tube packaging, helped it stand out in the burgeoning wargaming market. While not a massive commercial success on the scale of later games, its dedicated fan base and reputation for elegant design solidified its legacy as a foundational and influential title in the science fiction wargaming genre. It would also set the groundwork for the next game by GDW and in turn allow the company to work on Traveller.

Released in 1973 by GDW, Drang nach Osten! ("Drive to the East!") was a landmark board wargame that simulated Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Designed by Rich Banner and Frank Chadwick, the game was the first in what would become the extensive Europa series, a planned comprehensive simulation of World War II in Europe. Characterized as a "monster game," it featured an unprecedented scale with five large map sheets that, when combined, covered the Eastern Front from Poland to Stalingrad, and included over 1,700 counters. Drang nach Osten! was not only a massive undertaking in its design but also a significant commercial success, proving that complex, large-scale wargames had a viable market. The game was highly regarded and, when combined with its expansion Unentschieden, was even voted the most popular wargame in a 1976 poll by Simulations Publications Inc.

TSR, Inc. was originally established as Tactical Studies Rules in October 1973 by Gary Gygax and Don Kaye in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The initial goal was to publish the rules for a new type of game Gygax and Dave Arneson had been developing, but their first published product was a miniature wargame called Cavaliers and Roundheads. They soon brought on a third partner, Brian Blume, to help finance the publication of the game that would become their most famous title. The first print run of 1,000 copies of Dungeons & Dragons sold out in less than a year, establishing the company as a key player in the fledgling tabletop role-playing game industry. What emerged were the Little Black Books. Pocket‑sized and austere, they resembled technical manuals and adopted similar organizational logic: starship design sequences, subsector mapping procedures, encounter matrices, trade-and-commerce loops, and a character life-path that produced competent adults with careers, scars, pensions, and baggage. Where early fantasy RPGs often emphasized mythic spectacle, Traveller emphasized restraint and simulation. The result was a practical science‑fiction toolkit for referees: hexes, tonnage, jump fuel, starport classes, and the recurring problem of servicing a ship mortgage.

Role-playing games were already on the minds of GDW. A medieval miniatures wargame called Chainmail was developed by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren, who published it in 1971. This miniature rules set had a fantasy supplement included that added elements like wizards and dragons. Without a corporate backer, it had limited distribution but was influential far outside of its market exposure. The market success of Dungeons and Dragons, though, made GDW take notice of the potential of following up Triplanetary with its own RPG.

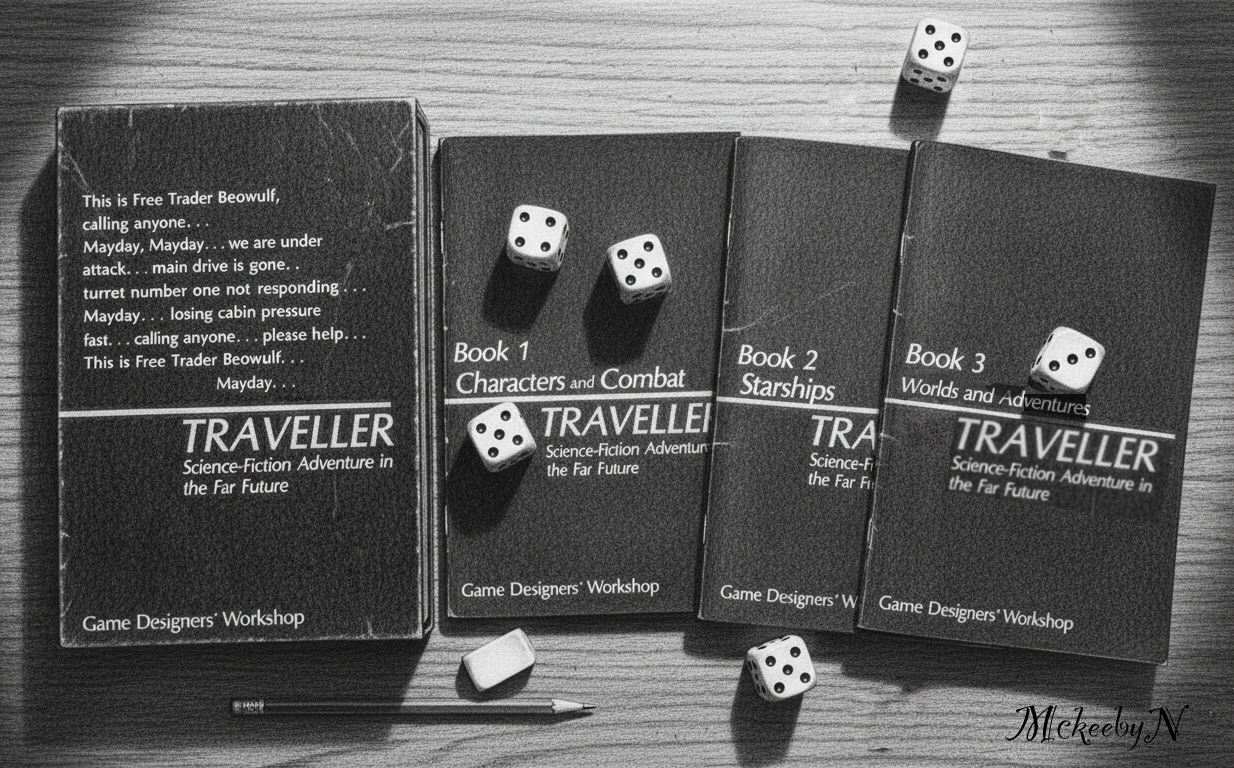

The Little Black Books

The original 1977 edition of the science fiction role-playing game Traveller was released by Game Designers' Workshop (GDW) and immediately drew comparisons to the early format of Dungeons & Dragons. Much like D&D's three-volume box set, Traveller was published as a set of three small, black booklets, each dedicated to a different aspect of the game: Book 1: Characters and Combat, Book 2: Starships, and Book 3: Worlds and Adventures. This modular format, along with the game's division of responsibilities between a "Referee" (the Game Master) and the players, mirrored the established model for tabletop RPGs.

However, Traveller set itself apart with a truly unique and influential character creation system. Instead of simply allocating points or rolling for stats, a character's life was simulated through a series of "terms," often representing four years, starting at age 18. Players would roll to determine if their character was accepted into a military service, went to college, or entered another career path. Through each term, the character would gain skills, rank, and possibly a lot of debt, with the risk of dying in the process. The system was designed so that a character's life story and abilities were largely in place before the first session began. As a result, characters often began play as grizzled veterans, not neophyte adventurers.

Publishing the original Traveller books in a digest format offered significant advantages in terms of cost, production, and distribution, which were crucial for a small company like Game Designers' Workshop (GDW). The digest format—a smaller size, roughly 5.5 x 8.5 inches—required less paper per unit, a direct and substantial cost saving on raw materials. This smaller size also allowed for more efficient use of printing press sheets, as more pages could be imposed onto a single sheet, reducing both printing time and the overall cost of a production run. For a niche product with a limited target audience, these cost-saving measures were essential to make the game economically viable.

In addition to the physical format, the aesthetic choices made for the books' covers further optimized production costs. The original Traveller books are known as the "Little Black Books" (LBBs) because of their solid black, text-only covers. This design choice was a pragmatic one, as using a single, solid color like black was far cheaper than printing complex, multi-colored artwork. It eliminated the need for expensive four-color process printing and reduced the likelihood of production errors like color misalignment. This simple, elegant, and low-cost design became a signature feature of the game, helping GDW keep the price of the product affordable for hobbyists.

The small size and light weight of the digest format also offered major advantages in distribution. Smaller, lighter products are less expensive to ship, both in terms of postage and in the physical space they occupy in shipping containers. This was particularly important for a game that was distributed through hobby shops and mail-order, where shipping costs could be a significant barrier. The compact size of the books also made them easier to store and display on retail shelves, taking up less space and allowing retailers to stock more copies. These logistical benefits helped GDW get its product into the hands of players more efficiently and affordably, contributing to the game's early success, and is often cited as one of the elements most missed by players in the release of later editions.

Expansion of the Universe

After the initial three core rulebooks, Game Designers' Workshop (GDW) leveraged the same affordable digest format to expand the universe and gameplay of Traveller. This strategy allowed them to create a modular and ongoing product line. They developed the Imperial Canon with the publication of the Spinward Marches subsector book, establishing a detailed setting for adventures beyond the core rules. This provided Referees with a ready-made region of space to use in their campaigns, filled with star systems, trade routes, and political factions.

In addition to expanding the setting, GDW also used the same "little black book" format to publish supplements that expanded character creation. Book 4: Mercenary and Book 5: High Guard were released to provide players with more specialized career paths beyond the basic ones in Book 1. Mercenary offered detailed rules for characters joining military units, with specific tables for combat skills, ranks, and specialized equipment. High Guard provided a comprehensive system for characters who chose a career in the Imperial Navy, including rules for commanding starships and specific ship-related skills. This approach of incrementally adding new career options in separate books allowed players to deepen their character's background and abilities without requiring an entirely new rulebook.

The original Traveller game, even in its most basic form, implicitly assumed a rich, detailed universe. The character creation process itself introduced players to a galactic empire known as the Imperium, with established institutions and career paths for its citizens. Players could join the Imperial Navy or the autonomous Scouts, a civilian service of explorers and information brokers, or even come from a background as a Noble. The game's technology was grounded in a hard science fiction aesthetic, with common items being relatable and functional. While the jump drive was the fantastic element that made interstellar travel possible, the game's focus on cargo, trade, and starship maintenance gave the world a pragmatic, lived-in feel, laying a strong foundation for a detailed setting.

This implicit setting was formalized with the 1978 release of the Spinward Marches supplement. This book provided a detailed subsector of the Third Imperium, giving referees and players a concrete, pre-made universe to explore. It included star charts, detailed information on star systems, and a rich political backdrop of a contested frontier region. This publication proved to be a pivotal step, as the Spinward Marches quickly became the canonical world system for all official Traveller products, providing a consistent and expansive sandbox for campaigns that was far more detailed than anything the core books could offer.

The detailed expansion of the Imperium continued in the pages of the Journal of the Traveller's Aid Society (JTAS). The first issue of this periodical was released in September 1979, and it became the primary vehicle for GDW to flesh out the game world. Each issue provided new rules, adventures, and in-depth articles that built on the history, politics, and technology of the Imperium. JTAS not only deepened the lore of the Spinward Marches but also introduced new sectors and alien races, collectively creating a vast and comprehensive universe that would be explored in subsequent supplements for years to come. JTAS would provide material for further core books, including Book 6: Scouts (1983), Book 7: Merchant Prince (1985), and Book 8: Robots (1986).

Mega Traveller

Game Designers' Workshop (GDW) moved away from the "little black books" for Traveller in 1987 with the release of MegaTraveller due to the need for a more comprehensive and streamlined rule system. The original 1977 edition, comprised of three small, 48-page booklets, was designed for a rules-light game where the referee was expected to create their own universe. However, over the decade that followed, the setting of the Third Imperium grew in complexity, with a multitude of supplementary books expanding on the lore and adding new rules. This expansion made the original, fragmented format impractical for new and old players alike.

The shift to a larger, single-volume format was a direct response to the game's evolution. The "Rebellion" metaplot, a major storyline GDW wanted to introduce, necessitated a unified ruleset to handle the large-scale conflicts and political machinations of the setting. The new format allowed GDW to consolidate the previously scattered rules and lore into a cohesive game system. This change also aligned Traveller with the prevailing industry standard for tabletop role-playing games at the time, which had largely moved away from small booklets and toward larger, more detailed core rulebooks. The transition from the iconic little black books to the larger, more conventional format marked a new era for Traveller, one that embraced its rich, detailed setting and provided a more accessible entry point for players.

MegaTraveller was built around a major storyline called "The Rebellion," which saw the collapse of the Third Imperium. For long-time players who had invested years in the static, stable universe of classic Traveller, this dramatic shift was a major shock. Many felt the setting they loved was being "ruined" and that the new, chaotic universe was confusing and less appealing. While GDW's intent was to make the setting more dynamic and create new campaign opportunities, the change alienated a significant portion of the existing player base.

While the goal of the new edition was to streamline the game, some aspects became more complex. The new starship construction and combat rules were particularly unwieldy, with many players finding them difficult to use without a spreadsheet. The release was also plagued with a significant amount of errata, which GDW attempted to address in later supplements. This constant stream of corrections was frustrating for players and gave the impression of a rushed and unfinished product.

Traveller 2300 AD or 2300 AD

Game Designers' Workshop's (GDW) Twilight: 2000 was a highly successful military role-playing game that envisioned a post-nuclear war Europe. Released in 1984, the game was a critical and commercial hit, praised for its detailed, realistic mechanics and grim, survivalist tone. Players assumed the roles of American soldiers cut off behind enemy lines in a devastated Poland, blending military strategy with a desperate struggle to survive. Its success created a new and loyal player base for GDW, distinct from the science fiction fans who followed Traveller. GDW recognized an opportunity to capitalize on this success and bridge its two audiences by creating a new game that served as a "sequel" to the Twilight: 2000 timeline, thus providing a logical progression for its military players while offering a different type of science fiction for its broader fanbase.

This effort led to Traveller 2300, released in 1986. The game was an attempt to create a "hard sci-fi" version of Traveller, specifically designed to fill a perceived niche for a more realistic and scientifically grounded space role-playing experience. It was deliberately stripped of the "space opera" elements that defined the Third Imperium, such as ancient alien empires, psionics, and the free-wheeling, galactic-spanning nature of the classic game. Instead, Traveller 2300 presented a grittier, more nationalistic future where nations like the United States, France, and a resurgent Germany were the primary colonizing powers. The technology, including the stutterwarp drive, was designed to be more limited and plausible, reflecting a less advanced future than the centuries-old Imperium. The goal was to attract the Twilight: 2000 players with a familiar, plausible future history while simultaneously offering a new, more grounded alternative for Traveller fans.

Traveller 2300, later renamed 2300 AD, was a critical success. Its ruleset was generally regarded as clearer and more polished than the later MegaTraveller, and its supplements were well-edited with strong storytelling. The game's emphasis on realistic physics and geopolitical intrigue resonated with a dedicated group of players. However, despite its critical acclaim, the game failed to capture a large enough market share. The name "Traveller" confused existing players who were expecting the Third Imperium, and the new game failed to fully convert the Twilight: 2000 fanbase. Its lack of commercial success eventually led GDW to refocus on its core Traveller line, and 2300 AD was ultimately discontinued, a testament to its quality but also to the difficulty of breaking into a saturated market with a different kind of product.

Traveller: The New Era (1993)

Following the mixed success of both MegaTraveller and 2300 AD, GDW made a final attempt to unify its science fiction lines with the release of Traveller: The New Era in 1993. This edition was designed to serve as both a sequel to the Rebellion storyline of MegaTraveller and a bridge to the post-apocalyptic setting of Twilight: 2000. The game took place in a shattered Third Imperium, a mere shell of its former self, with scattered polities struggling for survival in the aftermath of the Rebellion and the subsequent "Virus," a cybernetic plague. This dark, gritty tone was an explicit effort to attract the Twilight: 2000 player base, who were accustomed to a world of survival and limited resources. The goal was to consolidate GDW's science fiction offerings under one unified brand and rule set, as a direct solution to the market fragmentation caused by the two previous games.

Traveller: The New Era was innovative in its design but also plagued with problems. It introduced a completely new, integrated rule system that was intended to be compatible with GDW's other military games, particularly the third edition of Twilight: 2000. This meant that rules for things like vehicle combat and personal skills were now aligned, making it theoretically possible to use material from one game in the other. However, the new ruleset was a significant departure from the classic Traveller mechanics, alienating many longtime fans who preferred the older system. The game's setting, which was even darker and more chaotic than MegaTraveller's Rebellion, also proved to be a turn-off for some players. While it was a bold step to modernize the game and its mechanics, the changes were too radical for a fanbase already hesitant about the direction of the game line.

The Earthquake in the Industry

TSR's financial struggles in the 1990s were a complex culmination of internal mismanagement and wider industry shifts, serving as a cautionary tale for the entire tabletop gaming industry. The company's collapse demonstrated that even a market leader with a massively successful product like Dungeons & Dragons could fail if it didn't adapt to a changing landscape.

TSR was never a financially stable company, even during its peak. It often relied on a risky business model that involved taking out massive loans from distributors like Random House. The distributor would advance TSR money upon receiving product, with a high return rate. As TSR began overprinting products and creating too many different game settings and product lines, the return rate soared, and the company was left with a crushing debt it couldn't repay. A notable example of this was the overprinting of the DragonStrike board game, which sold well but still resulted in a net loss due to the excessive print run. This overextension, coupled with a series of bad business decisions—such as investing in unrelated ventures like needlepoint kits—fractured their core audience and drained resources.

The tabletop gaming industry of the 1990s was undergoing a profound transformation. The rise of collectible card games (CCGs), particularly Magic: The Gathering, was a seismic event. Hobby shops, which operated on limited capital, had to choose between stocking the latest D&D supplement or the new, highly profitable Magic sets. The CCG market was a "crack for gamers" in the words of one industry observer, with its booster pack model encouraging repeat purchases and its tournaments fostering a competitive play environment. This new type of game siphoned off a massive portion of the tabletop market, leaving many traditional RPG companies, including TSR, in a difficult position.

What did this have to do with GDW and Traveller? TSR’s downfall was not an isolated incident. It was the most visible example of a larger trend that nearly destroyed the entire tabletop RPG industry and ended the hobby completely. Other major publishers of the era, such as Avalon Hill and West End Games, also faced severe financial difficulties or went out of business. This reflected the failure of many older companies to adapt to new market demands, the rise of powerful new competitors, and a fundamental shift in how games were sold and consumed. The financial troubles of these companies were a clear signal that the old ways of doing business—relying on a handful of large-box releases and a steady stream of supplements—were no longer viable. The acquisition of TSR by a young, agile company, Wizards of the Coast, was the final chapter in this story, demonstrating that innovation and a better understanding of the modern market were essential for survival.

GDW would not survive this earthquake.

The end of Traveller, or is it?

Despite its quality, Traveller: The New Era could not save GDW from its ultimate demise. The company had been struggling financially throughout the early 1990s due to a variety of factors, including a change in the book distribution industry that heavily impacted their cash flow. The lack of a major commercial hit, compounded by the fragmentation of its product lines, further exacerbated the company's financial woes. While The New Era received critical praise for its elegant rules and compelling storyline, it failed to sell in sufficient numbers to stabilize the company. In 1996, after years of financial struggle, GDW ceased operations, bringing an end to the era of Traveller: The New Era and the company's ambitious attempts to unify its diverse role-playing game franchises.

The closing of Game Designers' Workshop (GDW) in 1996 was not a sudden event, but the culmination of years of financial struggles and an inability to adapt to a rapidly changing industry. While the company was lauded for its creativity and the sheer volume of its output—publishing a new product, on average, every 22 days for 22 years—it never achieved the financial stability of its main rival, TSR. A significant factor in its demise was the way the book distribution industry changed, with companies like Random House shifting their business practices. Distributors began demanding that GDW buy back unsold products, creating a massive financial burden that a company of its size could not sustain.

The company’s product line, while critically acclaimed, was also a contributing factor. GDW had a habit of creating numerous, distinct lines, such as the Traveller and Twilight: 2000 franchises, along with a wide variety of historical board games. While this allowed them to reach different segments of the market, it also fragmented their resources and audience. The final major attempt to unify these product lines, Traveller: The New Era, was a bold creative move but failed to sell in large enough numbers to reverse the company's fortunes. The core Traveller fanbase was already fracturing, and the new rule system, while elegant, was a bridge too far for many players who were comfortable with the older mechanics.

Ultimately, GDW’s downfall was a classic case of a company that was great at design but poor at business. The company simply ran out of money. Its founders and key designers, including Frank Chadwick, Marc Miller, and Loren Wiseman, were highly respected for their work, and many of their game lines would eventually be picked up by other publishers. However, the financial reality of the mid-1990s, with the rise of collectible card games and the consolidation of the hobby market, was a challenge that GDW could not overcome. On February 29, 1996, GDW officially ceased operations.

RevivalsUltimately, the legacy of Traveller stands in stark contrast to that of its once-dominant rival, Dungeons & Dragons. While D&D faced a near-extinction event due to TSR's financial collapse and was only saved by being acquired by a corporate giant, Traveller's fate was far more decentralized. Following the demise of GDW, the game's original creator, Marc Miller, reclaimed the rights to his creation. This led to a series of strategic revivals that kept the game alive and in the hands of its dedicated fans, rather than at the mercy of a single mega-corporation.

The post-GDW era of Traveller was defined by this splintered but persistent approach. Loren Wiseman, a long-time GDW designer, worked with Steve Jackson Games to produce GURPS Traveller, which adapted the Third Imperium setting to the popular GURPS universal rule system. This move not only preserved the setting but also introduced it to a new audience. At the same time, Marc Miller's own company, Far Future Enterprises, continued to produce new material, including the highly detailed and complex Traveller5, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to his original vision. While these different lines and editions did not have the market-dominating presence of D&D, they ensured the game's continuity.

This distributed model of publishing ultimately proved to be Traveller's greatest strength. When Mongoose Publishing entered the scene with a new edition in 2008, it benefited from the strong, albeit smaller, fan base that had been sustained by the efforts of Wiseman and Miller. Mongoose's editions, which were more closely aligned with the classic "little black books" and simplified mechanics, have been a commercial success and continue to put out a steady stream of products. Unlike D&D, which has endured its own share of controversy and has always faced the possibility of corporate-mandated changes, Traveller has thrived because its community has been a smaller, more fanatic group of players who have consistently supported its various incarnations. It is a testament to the fact that for a game to truly last, it must be cherished by its creators and its core audience, not just by the market at large.

1. Frank Chadwick has become an excellent science fiction author, writing How Dark the World Becomes and Chain of Command, which are published by Baen Books.

2. As an aside, Rich Banner often is not mentioned in gaming discussions, but his work as a graphic designer would be essential in making gaming mainstream, a fact reflected in his winning the Charles S. Roberts Award for Best Graphics in 1976 and a H.G. Wells Award for Best Historical Figure Series in 1979. As of the writing of this article, he remains active with the classic Europa series, several of which he helped design.

3. After GDW closed in 1996, he worked with Steve Jackson Games as art director and as the line editor for GURPS Traveller. He was inducted into the Origins Hall of Fame in 2003 and was featured in Flying Buffalo's 2010 Famous Game Designers Playing Card Deck. Loren Wiseman passed away on February 14, 2017.

Traveller Little Black Books The term "Little Black Books" (LBBs) is most commonly associated with the first edition of Traveller published by Game Designers' Workshop (GDW). The initial boxed set contained three core rulebooks. GDW then published many more supplements and adventures in the same small, digest-sized format.

- Here is a comprehensive list of the original GDW Traveller LBBs, categorized for clarity.

Core Rulebooks (The Original Boxed Set)

- Book 1: Characters and Combat (1977)

- Book 2: Starships (1977)

- Book 3: Worlds and Adventures (1977)

- Book 0: An Introduction to Traveller (1981)

- Book 4: Mercenary (1978)

- Book 5: High Guard (1979)

- Book 6: Scouts (1983)

- Book 7: Merchant Prince (1985)

- Book 8: Robots (1986)

- S1: 1001 Characters (1978)

- S2: Animal Encounters (1979)

- S3: The Spinward Marches (1979)

- S4: Citizens of the Imperium (1979)

- S5: Lightning Class Cruisers (1979)

- S6: 76 Patrons (1980)

- S7: Traders & Gunboats (1980)

- S8: Library Data (A-M) (1981)

- S9: Fighting Ships (1981)

- S10: The Solomani Rim (1981)

- S11: Library Data (N-Z) (1982)

- S12: Forms & Charts (1982)

- S13: Veterans (1983)

- A0: The Imperial Fringe (1981)

- A1: The Kinunir (1982)

- A2: Research Station Gamma (1983)

- A3: Twilight's Peak (1984)

- A4: Leviathan (1984)

- A5: Trillion Credit Squadron (1986)

- A6: Expedition to Zhodane (1986)

- A7: Broadsword (1986)

- A8: Prison Planet (1987)

- A9: Nomads of the World Ocean (1987)

- A10: Safari Ship (1988)

- A11: Murder on Arcturus Station (1988)

- A12: Secret of the Ancients (1988)

- A13: Signal GK (1989)

- D1: Shadows / Annic Nova (1980)

- D2: Mission on Mithril / Across the Bright Face (1981)

- D3: Argon Gambit / Death Station (1982)

- D4: Marooned / Marooned Alone (1983)

- D5: Chamax Plague / Horde (1984)

- D6: Night / Divine Intervention (1984)

- D7: The Perruques / Stranded (1985)

- AM1: Aslan (1984)

- AM2: K'kree (1984)

- AM3: Vargr (1985)

- AM4: Zhodani (1985)

- AM5: Droyne (1986)

- AM6: Solomani (1986)

- AM7: Hivers (1987)

- AM8: Damans (1988)